CAPOEIRA IN THE TERREIRO OF MESTRE WALDEMAR

Author: Eunice Catunda

Translation of the text of the article below the images.

Automatic translation, thanks for understanding.

Page 16:

Any artist who does not believe in the fact that only the people are the eternal creator, that only to them can come the strength and the true possibility of artistic expression, should attend a Bahian capoeira. There, the creative force is evident, vigorous, freed from the petty prejudices of academicism, having life itself as its primordial and sovereign law, which is expressed in gestures, in music, in poetry. There the magnificent and beautiful life is expressed, in no way altered by the limited capacity of primitive musical instruments, to which it adapts without being diminished.

The sense of collective achievement, the very essence of the art, is revealed in the triple aspect of capoeira, which is a fusion of three arts: music, poetry and choreography.

Capoeira in Bahia is what has never ceased to be the real art: not entertainment, but a necessity. In fact, it is one of the factors which accounts for the force a thousand times more lively of popular art when it is compared to highbrow music: this functional character, this aspect of imperious necessity possessed by all art that the people worship. While scholarly music sounds more and more out of tune, it still turns out to be mere sybarite pleasure, functionless, useless.

In Bahia, the art of capoeira is a Sunday activity, as normal and appreciated as our great national sport, football. And those who exercise it are, for the most part, the workers: construction workers, market porters, people with a definite profession, who spend the whole week on the hard "hitchhiking", struggling to guarantee their daily bread, for them yourself and for your family. Bahian capoeira is not like that of Rio, an art cultivated almost exclusively by the lumpen-proletariat, an art persecuted by the customs police as dangerous, provoking crimes and drunkenness. In Bahia, it is grown by healthy people; it is the art of combative people, without anything morbid or harmful.

The ritual, the tradition that capoeira participants follow, is very strict. The master is the connoisseur of tradition. Therefore, he is also the highest authority. He supervises the whole group, determines the music, the tempo, takes the turns or appoints the person to do so. He is also the one who determines the duration of each dance, watch in hand. The novice candidates dance among themselves. But when a dancer is noticed, the Master dances with him, signaling him, by this distinction, to the attention of veterans, novices and the public. This authority from Master is one of the most wonderful and moving things I have seen. The respect shown to him by the community, the affection with which it surrounds him, would make the envy of more than one conductor of classical music. This proves that the spirit of discipline is more alive among the coarse and uneducated people of our country, when they organize themselves, than among the upper classes, already more accustomed to the organization resulting from their own education and exercise of cultural activities and that, therefore, even, they would have a greater obligation to understand the need and importance of discipline in the community. Sometimes, however, the Master never abuses his rights. No dictatorial power is granted. He knows that his authority emanates from the community itself and behaves as an integral part of it. A fine example of modesty that I also observed in the Bahian terreiro, which I had already observed years ago on the coast of São Paulo in a colony of fishermen 3 kilometers from the village of Ubatuba, on the occasion of a "dance of S. Gonçalo" that happened there. In this one, the mistress was an old woman of seventy years, severe and indefatigable. But the "dance of S. Gonçalo" will be left for another article.

The Terreiro de Mestre Waldemar is located in the famous proletarian district of Liberdade. Densely populated neighborhood, unpretentious, forgotten by the town hall who cares about beautifying and taking care of only those parts of the city of Salvador that are in sight of the tourist. As for the Liberdade district, it is not for the "gringo" to see. Like any popular district, it has no pavement, it is full of ditches where, in rainy weather, the water rots, enveloped in clouds of mosquitoes; their countless huts barely stand, and if they do, it is out of sheer stubbornness. Vendolas abound where you can buy everything from jabá to caninha. It is a neighborhood full of life and movement, brave and angry. On this sunny Sunday, the paths of Liberdade, where Alina Paim encountered the hunger and misery of an abandoned Bahian childhood, which she grew closer to and which contributed a lot to making her put her art at the service of the people, were even beautiful. . The bright colors of Bahia continued in the Sunday outfits of the city's youth. The bright light of day was reflected in the more relaxed faces of the workers and in the white smiles of the little black kids with their faces washed by the weekly bath, so difficult because of the precariousness of the practically non-existent toilets. …

When we arrived at the terreiro, the capoeira had already started. Two dancers squatting low to the ground, while two birimbaus and three tambourines accompanied with strange rhythms and sounds this magnificent and delightful dance, of combative and strong people. The dancers at the time were a market porter from Água de Meninos and a construction worker. The workman was all in white, the shoes shone, the shirt whitened. He was one of the best dancers. It is customary for the fine flower of capoeiristas to dance like this, “in white” as they say, to demonstrate their know-how. They reach the top of the dance with their hats on, and the skillful dancers boast that they leave the dance without a single spot of dirt on their clothes, clean and tidy as if they had not yet begun their work.

The circle of spectators, people from the neighborhood, friendly people whose only strangers were Maria Rosa Oliver and me, were soon electrified by the dance. We only became aware of time in the brief intervals between one dance and the next; and just like that to find that the sequel was taking too long…

The Capoeira dance is the symbolic representation of authentic old fights. In Capoeira de Angola, the dancers turn almost close to the ground, performing armrests, in a horizontal position, turning, sliding like eels and slipping under the opponent's body. The blows are confirmed by bows and by the exclamations of the assistants. In fact, without the precision of these moves, many of the hits would be lethal. This is the case of the famous blows of the head directed towards the chest and whose momentum is only stopped at the very last moment, when the head

Page 17:

of one of the dancers has already touched the body of the other. The latent violence is never unleashed and this extraordinary mastery of passion keeps the audience in an incredible tension of nerves, exciting everyone in a sort of almost indescribable collective hypnotism. Only those who have attended a demonstration of Capoeira de Angola will be able to understand the strength and the monstrous control required to perform each of these movements, without giving rise to any aggression, without losing the elegance and feline grace of each gesture. , absolutely measured, calculated by a sort of instinct, since the active elements are entirely given over to this art, apparently so impulsive and so spontaneous.

Another characteristic that stands out in Bahian capoeira is the fact that the two dancers, or the whole group, because sometimes there are several of them, two by two, perform with the same intensity. It is not like capoeira carioca, in which one of the companions remains motionless, in an attitude of defense, while only the other attacks, dancing around the enemy, giving him blow after blow. In capoeira de angola, neither of them stands still. On the contrary, they move like spindles, like shuttles! And the spirit of joy is always present. Despite the latent violence, hostility does not ensue. In the midst of all this there is immense brotherhood and joy. There are witty passes of cheerful, smiling dancers performing difficult and extremely dangerous steps and kicks. And among the assistants, burst out great laughter... I have never seen, in national or foreign ensemble dances, such ravishing beauty, combined with such speed, precision and restrained strength, dominated by discipline and complete clarity.

We had the opportunity to admire a seven-year-old boy who danced with Mestre Waldemar himself, whose pupil he is, and with that expert worker of whom I have already spoken. You can't imagine how moving it was to accompany the fragile, skilful, serious little child, in competition with the eldest, whose face lit up with an affectionate but not at all complacent smile. Concentrated, the boy applies head kicks and rasteiras, slipping with agility and agility rasteiras and head kicks from the master, aware of his dignity as a future capoeirista, a future popular artist, undisturbed, under the looks and exclamations spectators.

Now let's move on to the other aspect, which concerns the music.

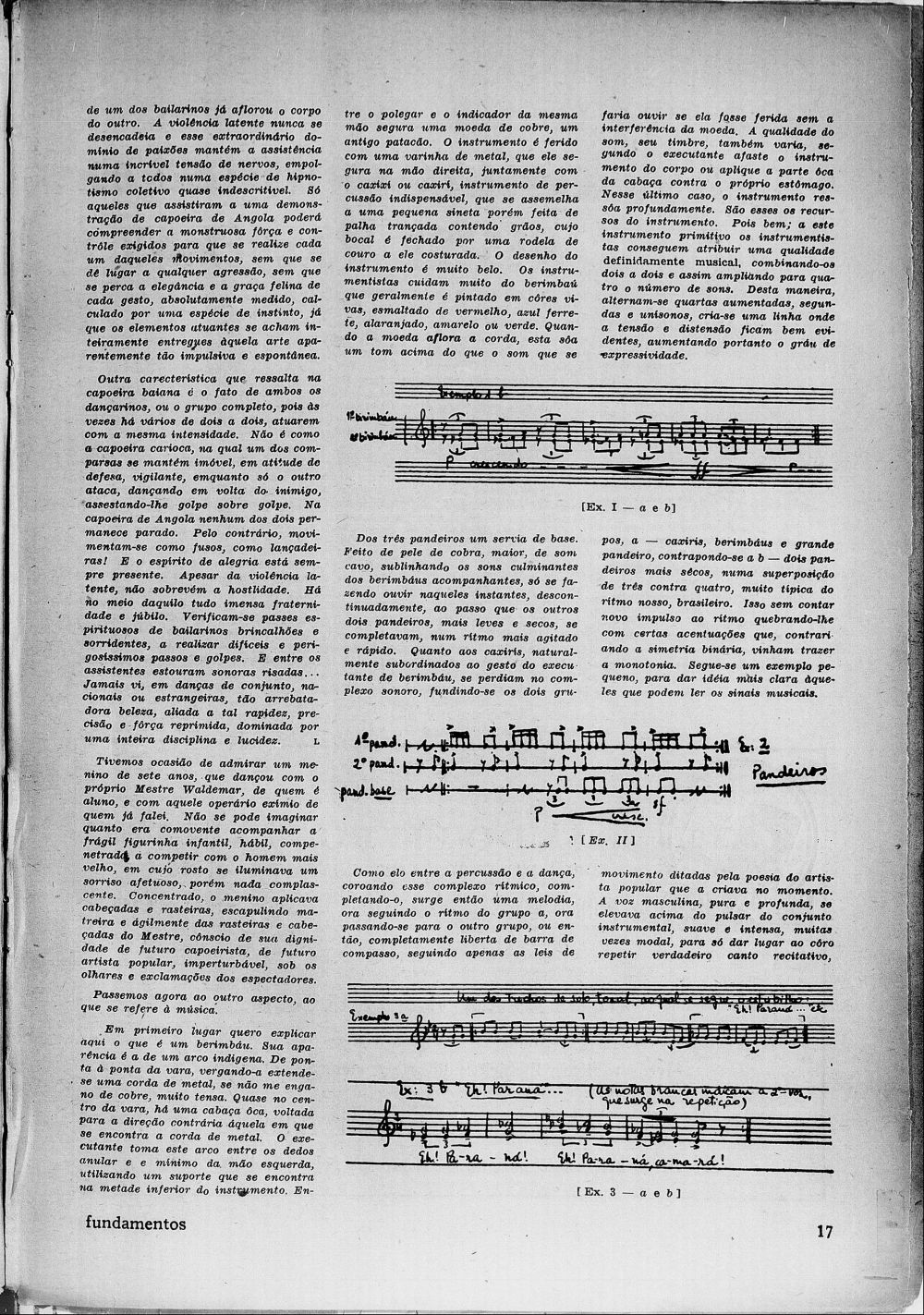

First I want to explain what a berimbau is. Its appearance is that of a native bow. From end to end of the rod, bending it, stretches a metal cord, if I'm not mistaken in copper, very tense. Near the center of the stick is a hollow gourd, opposite the metal string. The player takes this bow between the ring finger and the little finger of the left hand, using a support which is in the lower half of the instrument. Between the thumb and forefinger of the same hand, he holds a copper coin, an old patacão. The instrument is wounded by a metal rod, which he holds in his right hand, as well as the caxixi or caxiri, an indispensable percussion instrument, similar to a small bell but made of braided straw containing grains, whose mouth is closed by a leather ring sewn on it. The design of the instrument is very beautiful. The instrumentalists take great care of the berimbau, usually painted in bright colors, enamelled in red, blue, orange, yellow or green. When the coin hits the string, it sounds a pitch higher than the sound that would be heard if injured without the interference of the coin. The quality of the sound, its timbre, also varies depending on whether the player moves the instrument away from his body or presses the hollow part of the calabash against his own belly. In the latter case, the instrument resonates deeply. These are the characteristics of the instrument. Well; To this primitive instrument, the instrumentalists manage to attribute a distinctly musical quality, combining them two by two and thus bringing the number of sounds to four. In this way, augmented fourths, seconds and unisons are alternated, creating a line where tension and distension are very evident, thus increasing the degree of expressiveness.

Remarks [Ex. I - a and b]

Of the three tambourines, one served as a base. In snakeskin, larger, with a hollow sound, emphasizing the culminating sounds of the accompanying berimbáus, only heard at these times, discontinuously, while the other two tambourines, lighter and more dry, complemented each other, in a more agitated and rhythmic rhythm. As for the caxixis, naturally subordinated to the gesture of the berimbau player, they were lost in the sound complex, merging the two groups, a — caxixis, berimbau and large pandeiro, opposing b — two sharper tambourines, in a superposition of three against à four, very typical of our Brazilian rhythm. Without forgetting a new impulse to the rhythm, breaking it with certain accentuations, contrary to the binary symmetry which came to bring monotony. A small example follows, to give a clearer idea to those who can read the musical signs.

Remarks [Ex. II]

Hyphen between percussion and dance, crowning this rhythmic complex, completing it, a melody then emerges, sometimes following the rhythm of group a, sometimes passing to the other group, or, completely freed from the bar bar, following only the laws of movement dictated by the poetry of the popular artist who created it at the time. The male voice, pure and deep, rose above the pulsation of the instrumental ensemble, soft and intense, often modal, to leave room only for the choir repeating a real recitative song,

Notes [ Ex. 3 — and a b ]

Page 18:

Then the voice continued, flourishing on the same base, never repeating, almost impossible to write precisely by non-mechanical means.

Notes [ Example 4 ]

The soloists alternated, giving the melody the characteristic characteristic of their human temperament. Some were more alive, more spiritual, while others were dreamy, simple. But, all the texts, deeply poetic.

I well remember a voice that rose to sing the beauty of sloops under full sail, praising the generous sea and the wind that carries them. He described the wind picking up clouds and then dissolving them into small drops of rain on the white sail of the sloops he was packing. It is popular poetry that was present in the triple splendor of this unique art that is Capoeira de Angola. And to all this the choir continued to respond through the mouths of all the assistants and participants: "Eh! Paraná, eh! Paraná, camará..." while the dancers continued to meander, turn, turn, divert their body headbutts, laughing high, jumping, springy like cats. And we, prisoners of the beauty of the sung texts, which brought tears to our eyes, prisoners of the people who, even without wanting to be loved, in this modest terreiro of the Liberdade district and wherever they are.

This is what I had to say about the most grandiose and violent manifestation of folk art that I have ever seen and that has affected me the most. I learned a little more from her, there I saw again the power of expression of our people who abandon themselves to art like a child, naively. But this is always simple, grandiose, generous and prodigal of its infinite riches.

I really wanted to see my friends there: Santoro, Guerra Peixe, Camargo Guarnieri who has seen and heard much more than us, Eduardo de Guarnieri who will understand the wonderful message of people's artists in action.

Writers, painters, sculptors and poets, you must look for Bahia! The Peace that took me there, the Peace that opened the paths of culture and Hope, should take us all, often through this endless Brazil, full of creative people, forgotten or forgotten folklore , full of social problems and struggles in which we have a duty to participate.

I also wanted to see our enemies there. Many Europeans walk around, looking at Brazil from the top of their noses, creating confusion and thinking that folklore is only "Casinha Pequeninha" and parlor curiosity to satisfy the cosmopolitan appetite of "gringos", it is just the good neighbor policy. Many artists who take advantage of people to climb and then start kicking them with the screwed boots of their genius...

If we all found ourselves together in this Bahian terreiro, friends and enemies, we who believe would communicate with a simple smile or a look of pride. And the others that we would crush with our hope for the future with the strength of the people to which we belong and who are liberating themselves. They would see that their world dies, while ours appears, full of the splendor of Capoeiras de Angola, Danças de S. Gonçalo, Maracatus, Reizados, Festas do Divino and much more of everything that makes us the next day that sings" about which Paul Vaillant-Couturier spoke.

In the distance, beyond the borders of the world-that-has-already-ended, one could see the impotent envy transpiring in the eyes of the cosmopolitan lice, despite the dark glasses of the "ray-ban" behind which they seek an impossible refuge. , in the blindness of those who do not want to see...

Source: VelhosMestres.com

Capoeira News

Capoeira News

Capoeira Instruments

Capoeira Instruments

Capoeira's Masters

Capoeira's Masters

Capoeira, History, Archives, Documents, PDF

Capoeira, History, Archives, Documents, PDF

Roda of Capoeira on the beach with Mestre Pastinha and his students 1965

Roda of Capoeira on the beach with Mestre Pastinha and his students 1965

Emília Biancardi Ferreira

Emília Biancardi Ferreira

Complete documentary (INA.fr) -

Complete documentary (INA.fr) -

The great historian of Capoeira: Jair Moura

The great historian of Capoeira: Jair Moura

Inezil Penna Marinho, biography, PDF books

Inezil Penna Marinho, biography, PDF books